At the Human Rights Council in Geneva, Ms. Bachelet maintained that the inability of countries to uphold fundamental liberties - such as justice, quality education, decent housing and decent work - had “undermined the resilience of people and States”.

Multiple shocks

This had left them exposed to what she called a “medical, economic and social shock”, highlighting that an additional 119 to 124 million people had been pushed into extreme poverty in 2020, before citing Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) data indicating that food insecurity rose to an unprecedented 2.38 billion people.

“Vital gains are being reversed – including for women's equality and the rights of many ethnic and religious minority communities and indigenous peoples,” the High Commissioner for Human Rights said, adding that “cracks in the social fabric of our societies are growing wider” with “huge gaps between rich and poorer countries (that) are becoming more desperate and more lethal”.

“We must ensure that States’ economic recovery plans are built on the bedrock of human rights and in meaningful consultation with civil society,” she said. “There must be steps to uphold universal health care, universal social protections and other fundamental rights to protect societies from harm, and make all communities more resilient.”

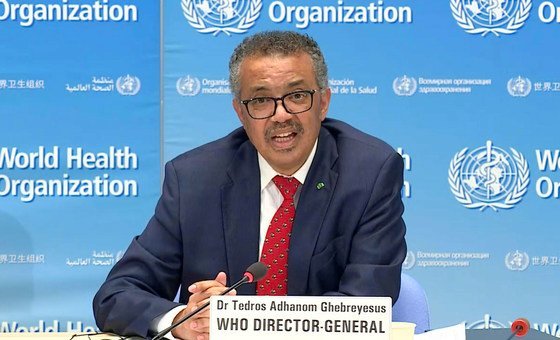

‘Crisis of vaccine inequity’

On the issue of glaring coronavirus vaccine and therapeutic shortages in many developing countries, the High Commissioner urged States to “act together, in solidarity”, to distribute the jabs.

“Today, hospitals in some regions have essentially collapsed, with patients unable to find the care they need, and oxygen almost completely unavailable,” she said, pointing to “a crisis of vaccine inequity (that) continues to drive deeper divides into the heart of the international community”.

Zooming in

Echoing those remarks, Nobel Laureate and economist, Professor Joseph Stiglitz, described how COVID-19 had barely affected those at the top end of the global economy, while those at the bottom have suffered massively in respect of their jobs, health and their children’s education.

The coronavirus has not been “an equal opportunity virus”, he insisted; “it has had a devastating effect on the bottom parts of our economy, our society. While those at the top, many of them have done very well. Most of them have been able to carry on, continuing their jobs on Zoom, continuing their incomes, almost without interruption.”

On the issue of COVID-19 vaccines, Professor Stiglitz reminded the Human Rights Council that access to them “is almost part of a right to life, and yet, access to the vaccines, while is very easy in the United States and another advanced countries, is extraordinarily difficult in emerging economies and almost impossible in most developing countries”.

As a basic human right, “there is no right more important than the right to life”, he continued, insisting that access to medicines was a basic human right “and that basic right today is being violated by the failure to give equal access or even any access to the vaccines”.

In a related debate at the Geneva forum, Member States heard that indigenous children and those with disabilities continue to be hit particularly hard by the COVID-19 crisis.

Assistant Secretary-General for Human Rights, Ilze Brands Kehris, also said that indigenous women and elders have been badly affected, in an annual discussion on the rights of indigenous peoples.

Victims of unequal health-care access

The pandemic had “exposed and exacerbated” the inequalities and systemic racism that they faced, Ms. Kehris said, adding that many indigenous people had died amid “unequal access to quality health care”.

The top human rights official noted that the pandemic had also impacted the resilience of indigenous languages and traditional knowledge.

This was concerning, she said, given the objective of the Sustainable Development Goals (or SDGs) to “leave no-one behind”.

Lack of consent

Echoing that message, UN Special Rapporteur on the rights of indigenous peoples, José Francisco Cali Tzay, expressed concern that post-pandemic recovery efforts by many States were continuing to have “negative impacts” on indigenous peoples.

“Nationwide measures to stop the pandemic are being applied to indigenous territories without their free, prior and informed consent and without taking into account the systemic barriers faced by recipients,” the Special Rapporteur said.

Some indigenous communities had set up their own COVID-19 resilience solutions, however.

Indigenous solutions

These include Brazil’s, Kuikuro people, who have formed partnerships with hospitals, set up their own health centre and hired doctors and nurses to stay with them and help with prevention, said Mr Tzay.

In Thailand, he continued, iKaren people have performed rituals by shutting down their villages and not allowing anyone to enter and in Bangladesh, the Mro people have put up a bamboo fencing at the entrance of their territory to isolate their villages.

“Rather than relying solely on government aid, indigenous peoples are coordinating community-level responses that include reconnecting with scientific knowledge and managing humanitarian and mutual aid networks,” he said.

“States must fulfil their obligations to provide support for protection plans elaborated by indigenous peoples in an autonomous manner.” https://news.un.org/en/story/2021/09/1101552