Lesconil, a salt-bitten fishing port tucked into the coast of Brittany, in northern France, stirs slowly under the pale Atlantic dawn. Tide pools shimmer, breathing with the sea — undisturbed but for the cries of seabirds and a lone figure in yellow waders, knee-deep in a forest of seaweed. The man, Vincent Doumeizel, gently lifts a strand of Saccharina latissima from the brine, waving it above the waterline like a revolutionary banner.

“It’s not slimy,” he says of the olive-brown frond glistening in his fingers. “It’s magnificent.”

For Doumeizel, seaweed is more than a marine curiosity. This diverse family of green, red, and brown algae is a cornerstone of his life’s work – a vehicle for feeding the planet, restoring oceans, fighting climate change, and even replacing plastic.

It is, as he likes to say, “not just a superfood, but a super solution.”

A senior adviser to the UN Global Compact, a platform advocating for sustainable corporate practices, the 49-year-old Frenchman has become one of the faces of the so-called “seaweed revolution.”

In 2020, he co-authored The Seaweed Manifesto, a collaborative document involving the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), the World Bank and other partners. Its premise is bold: harness the humblest of marine organisms to tackle some of the planet’s most complex problems.

Algae, the manifesto argues, can help solve a quartet of crises – climate, environmental, food, and social. Doumeizel’s personal conviction borders on the messianic. “Undoubtedly,” he wrote in a 2023 book outlining his vision, seaweed is “the world's greatest untapped resource.”

© Courtesy of Vincent Doumeizel

Vincent Doumeizel sometimes speaks of “sea forests” rather than “seaweed” – a linguistic sleight of hand designed to counter the Western bias that sees seaweed as stinky pollution waste.

Algae against apocalypse

Long before trees shaded Pangaea and dinosaurs thundered across its land, seaweed was already swaying in the sunlit shallows of ancient oceans – a silent architect of Earth’s transformation. Born more than a billion years ago, marine algae were among the first complex organisms to harness sunlight through photosynthesis, oxygenating the atmosphere and shaping the conditions for multicellular life.

But Doumeizel is neither a marine biologist nor an agronomist. His background is in food policy.

“I came across world hunger during an early deployment to Africa,” he told UN News. “It left a strong mark.”

Seaweed first sparked Doumeizel’s interest on a subsequent trip to the Japanese island of Okinawa, whose residents have exceptionally long lifespans. He noticed that people there ate a lot of seaweed.

“It was delicious,” he recalled. “And visibly healthy.”

From the northeast Atlantic “sea spaghetti” (Himanthalia elongata), to the Indo-Pacific “green caviar” (Caulerpa lentillifera), and the ubiquitous “sea lettuce” (Ulva lactuca), algae are rich in vitamins, omega-3 fatty acids, fibers, and even proteins.

Humble and often overlooked, these marine vegetables may be one of our most underappreciated sources of nutrition. Despite covering more than 70 per cent of the planet, the ocean contributes only a sliver to the global food supply in terms of calories – a gap that seaweed could help close.

And while agriculture contributes to roughly a quarter of global greenhouse gas emissions, in part due to deforestation for pastures and crops, seaweed cultivation does not require any land, fertilizers or freshwater.

Recent research even suggests that feeding red seaweed to cows could reduce their methane emissions by up to 90 per cent – a potential game-changer in the fight against climate change.

The implications go far beyond the barnyard. The ocean has generated more than half the oxygen we breathe, and it absorbs about a third of all man-made emissions. Seaweed plays a part in this process, capturing more carbon per acre than land vegetation. Some species, like “giant kelp” (Macrocystis pyrifera), can grow at an astonishing rate of two feet per day, making them powerful carbon sinks.

Seaweed can also be extracted and transformed into bioplastics, biofuels, textiles, and even pharmaceuticals.

“We can change the paradigm by encouraging seaweed cultivation,” Doumeizel said.

© Courtesy of Vincent Doumeizel

Algolesko, off the coast of Lesconil, in Brittany, is one of the largest seaweed farms in continental Europe, with 150 hectares of organic Laminaria culture.

A growing, yet under-regulated industry

When we met Doumeizel in Nice ahead UNOC3, the shorthand by which the third UN Ocean Conference is known, he was coming from the launch, two days earlier, of his comic book. The Seaweed Revolution is a 128-page dive into the life of an algae enthusiast also named Vincent “involved with the UN Ocean Forum.”

In real life, Doumeizel is as passionate and buoyant as on his TED Talk videos or keynote addresses.

“I could eat those,” he says, holding up a pair of sunglasses — sleek, black, and entirely made from plankton. Perched on a sunlit ledge above the Mediterranean, Doumeizel becomes part showman, part prophet, as he unpacks a series of seaweed-born wonders: a biodegradable garbage bag that looks indistinguishable from plastic, a soft green T-shirt spun from algae fibers, and, with a grin, an edible copy of his own book, The Seaweed Revolution. “All of this,” he says, gesturing to the strange little tableau at his feet, “could be made of seaweed.”

While the world’s salty waters are home to 12,000 different known species of seaweed, so far humans are only able to actively cultivate less than a couple dozen of them – a practice known as kelp farming.

Algolesko, in Brittany, is one of the largest seaweed farms in continental Europe. The morning when Doumeizel could be seen lifting a brown algae from the Atlantic Ocean, he was doing so from the farm’s 150 hectares of organic culture.

As co-head of the Global Seaweed Coalition, which is roughly 2,000-members strong and hosted by the UN Global Compact, Doumeizel travels around the world for speaking engagements, from Patagonia to Tunisia, Madagascar, and Australia. Each stop is also an opportunity to explore local seaweed production.

According to a concept paper written by the UN ahead of Nice’s Ocean Conference, the seaweed industry is on the rise. Production of marine algae more than tripled since 2000, up to 39 million tonnes a year, the overwhelming majority of which comes from aquaculture. It has become a $17 billion market, and current investments in bio stimulants, bioplastics, animal and pet foods, fabrics, and methane reducing additives could add another $12 billion annually by 2030.

Yet the path forward is not simple. “There is generally a lack of legislation and guidance,” notes the UN document. “There are currently no Codex Alimentarius standards establishing any food safety criteria for seaweed or other algae.”

Doumeizel agrees. The global seaweed industry, he said, is still fragmented and largely dominated by Asia, where the production of nori, the kind of seaweed used in sushi, was already a hugely profitable business. But, he added, so much more could be done with the resource.

© Courtesy of Vincent Doumeizel

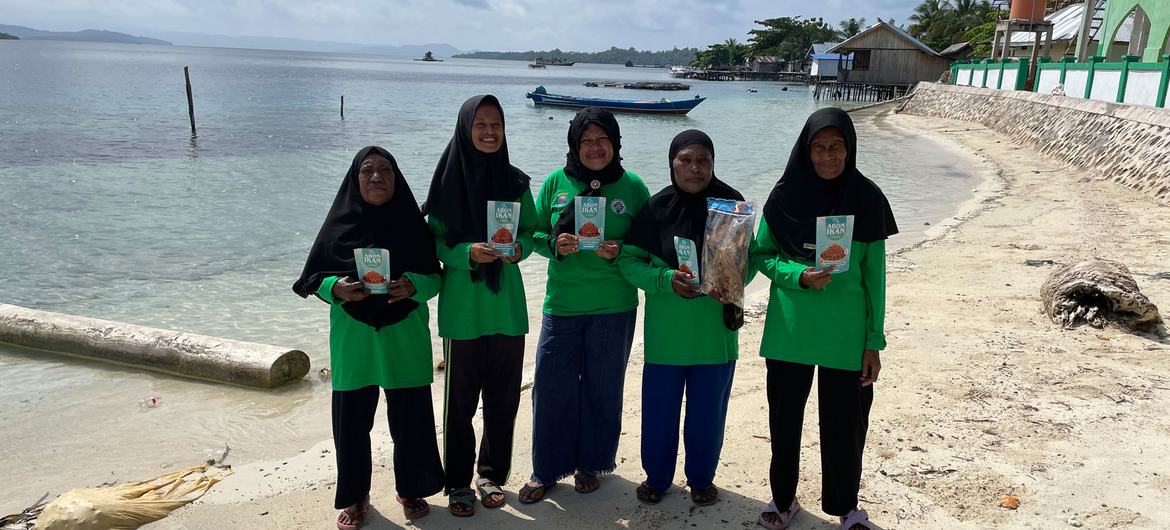

On the island of Zanzibar, the seaweed boom began with a surge in demand for food texturizers made of algae. Widows and single women quickly stepped up.

Reducing gender inequality

Beyond its environmental promise and nutritional punch, seaweed is quietly driving a feminist transformation. According to the concept paper, about 40 per cent of seaweed start-ups worldwide are led by women.

“In Tanzania, a largely patriarchal society, the seaweed trade has changed lives,” said Doumeizel. The boom began with a surge in demand for food texturizers made of algae. Widows and single women quickly stepped up. On the island of Zanzibar, seaweed is now the third-largest resource, and women retain nearly 80 per cent of the profits.

“They built schools. They sent their daughters to those schools. They fought for a place in the markets to sell their harvests,” Doumeizel said. “They even bought motorcycles.”

The ripple effects have reached the highest levels of power: the current President of Tanzania is a woman from Zanzibar.

But climate change is pushing the industry into deeper waters – quite literally. As sea temperatures rise, the algae can no longer be cultivated close to shore. “Now, women have to venture farther out,” Doumeizel explained. “But most don’t know how to swim or steer a boat.”

To help preserve both livelihoods, the Global Seaweed Coalition is funding a new initiative to teach women maritime skills – swimming, boating, navigation. “We have to make sure this revolution leaves no one behind,” the Frenchman said.

The threat of climate change

If seaweed offers a promising solution to climate change, it is also one of its quietest victims. As atmospheric carbon dioxide climbs, the ocean grows warmer and more acidic – conditions that are already eroding marine ecosystems and triggering the widespread loss of seaweed habitats.

In places like California, Norway, and Tasmania, more than 80 per cent of kelp expanses have vanished in recent years, driven not only by climate change, but also pollution, and overfishing.

In interviews, Doumeizel sometimes speaks of “sea forests” rather than “seaweed” – a linguistic sleight of hand designed to counter the Western bias that sees seaweed as stinky pollution waste rather than threatened organisms.

“Preserving them is just as necessary to life on Earth as saving the forests of the Amazon,” he wrote in his book.

At UNOC3, which opens on Monday, Doumeizel will unveil a new initiative: the creation of a UN Seaweed Task Force. Designed to consolidate global efforts around regulation, research, and development, the task force would bring together six UN agencies – the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), the Global Compact, the UN Environment Programme (UNEP), the UN trade and development body (UNCTAD), the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), and the UN Industrial Development Organization (UNIDO).

Its aim is ambitious: to give seaweed the institutional muscle it has long lacked. By centralizing expertise and setting global standards, the task force could help scale up the industry responsibly – and sustainably.

The proposal already has the backing of several countries, including Madagascar, Indonesia, South Korea, and France. Together, they plan to introduce a draft resolution at the UN General Assembly this fall, with a vote expected in 2026.

© Courtesy of Vincent Doumeizel

On the island of Zanzibar, seaweed is now the third-largest resource.

From bloom to boom

Sometimes, the revolution doesn’t arrive in neat rows of aquafarms. It comes in 6,000-mile-wide blobs.

In the spring of 2025, a vast bloom of sargassum – a free-floating brown algae known for its sprawling mats – blanketed the Atlantic, clogging beaches from the Gulf of Mexico to the shores of West Africa. Florida's shore became inundated with the plant, whose pungent smell was deterring tourists. Coastal communities scrambled to manage the deluge.

Yet, Vincent Doumeizel saw not just crisis but opportunity. “These massive blooms are caused by pollution and climate change,” he noted. “But if we manage and understand them properly, they could become a sustainable resource, turned into fertilizers, bricks, even textiles.”

The vision is part redemption, part alchemy. Turning oceanic overgrowth into solutions may seem far-fetched. But then again, so does the idea that seaweed could replace beef – or plastic.

Roughly 12,000 years ago in the Middle East, Homo sapiens ceased to be hunter-gatherers. “We became farmers cultivating plants to feed our animals and our families,” Doumeizel wrote in his book. “Meanwhile, at sea, we are still Stone Age hunter-gatherers.”

But what if we could farm the ocean – not to exploit it, but to heal it? It’s not just a rhetorical question. It’s an invitation. And perhaps, a final warning.

https://news.un.org/en/story/2025/06/1164131

https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/legalcode