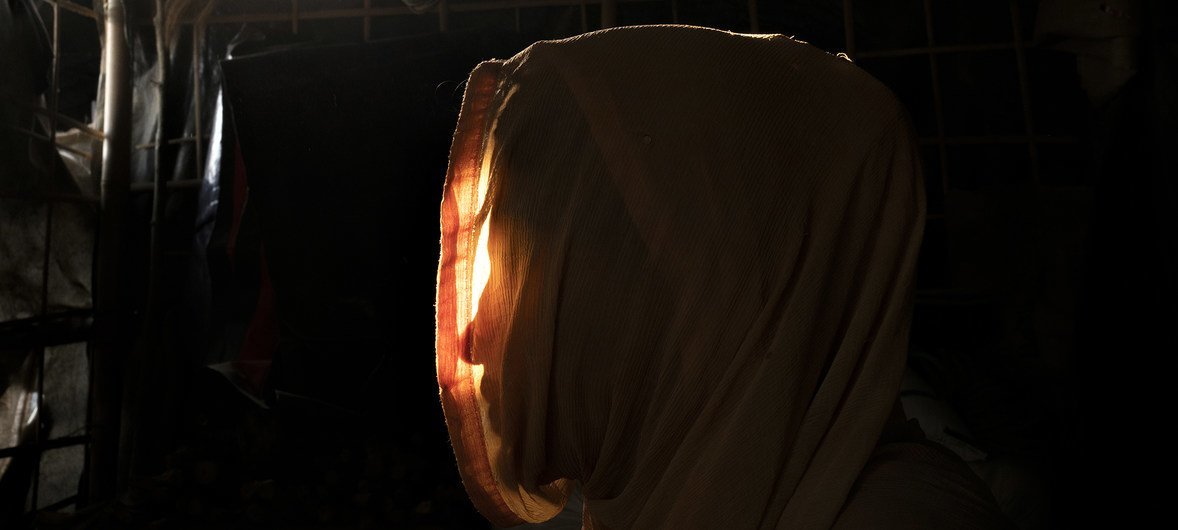

UNHCR/Roger Arnold

A Rohingya woman crosses the border from Myanmar into Bangladesh near the village of Anzuman Para in Palong Khali.

18 June 2018

Migrants and Refugees

Despite challenges brought on by the arrival of the monsoon season this month, United Nations agencies in Bangladesh continue to support nearly one million Rohingya refugees, including thousands of victims of sexual violence.

Members of the mainly-Muslim minority community began fleeing Myanmar’s Rakhine state last August following a military crackdown targeting extremists, during which homes were destroyed, men and boys killed, and countless women and girls raped.

In early May, UN News published a special report highlighting the concerns being voiced by several leading UN officials over the legacy of what Andrew Gilmour, UN Assistant Secretary-General for Human Rights, described as a “frenzy of sexual violence”.

On Tuesday, the world marks the International Day for the Elimination of Sexual Violence in Conflict, and we have been finding out how some of the survivors have been coping, now that dozens of children of rape have been born – and what UN agencies are doing to provide them with vital services and support.

“Sameera” (not her real name) is among the Rohingya refugees now sheltering in the crowded camps of the Cox’s Bazar region in south-eastern Bangladesh.

The 17-year-old had only been married for a couple of months when her husband was killed.

She was raped just days after his death, when three soldiers showed up at her door, together with two other Rohingya girls, who were also raped.

“As I will give birth to the baby, he or she will be mine, no matter who the father is,” she told the UN Children’s Fund (UNICEF).

‘Forgotten victims of war’

Since August, more than 16,000 babies have been born in the refugee camps, according to the UN agency.

It is difficult to determine exactly how many were conceived through rape, said Pramila Patten, the Special Representative of the UN Secretary-General on Sexual Violence in Conflict.

“You also have the stigma of a pregnancy as a result of rape which makes it very hard for (women) to come out openly with the fact of their pregnancy,” she told UN News last month, shortly after returning from a mission to the Kutupalong camp, one of the largest refugee camps in the world.

“And in fact, there are many reports from local Rohingyas that many girls, especially young adolescents, are actually hiding the fact of their pregnancy and will never seek medical care, for example, for the delivery.”

UNICEF has collected testimonies from several women and girls like “Sameera,” whose children are among what UN Secretary-General António Guterres has called the “forgotten victims of war.”

Conceived through conflict-related rape, these boys and girls grow up struggling with their identity, or fall victim to stigma and shame. At the same time, their mothers are marginalized or even shunned by their communities.

For the past three years, the UN has designated 19 June as the International Day for the Elimination of Sexual Violence in Conflict to promote solidarity with survivors.

Ms. Patten’s office is co-hosting an event at UN Headquarters in New York to mark Tuesday’s international day, where strategies will be discussed on how to change the perception that these children and their mothers are somehow complicit in crimes committed by the groups that violated them.

Midwives and monsoons

Back in Bangladesh, the arrival of the monsoon winds and rains just over a week ago is making life even more difficult for the Rohingya refugees and the humanitarians assisting them.

More than 720,000 Rohingya have arrived in Cox’s Bazar as of the end of May, according to the UN refugee agency (UNHCR), joining some 200,000 others who had fled earlier waves of persecution and discrimination.

UN agencies are responding to the overwhelming needs, though a $951 million humanitarian plan is less than 20 per cent funded.

Since the start of the crisis, the UN Population Fund (UNFPA) has deployed 60 highly skilled midwives to the area who are also trained in clinical management of rape and family planning counselling.

Nineteen women-friendly spaces have also been created in the camps.

UNFPA said key among “protection challenges” is scaling up assistance to survivors of gender-based violence, and other vulnerable populations, including through psychosocial support and counselling, and psychological first aid.

So far, 47,000 Rohingya mothers-to-be have received antenatal check-ups while 1,700 babies were safely delivered in clinics supported by the Fund.

UNFPA recently Tweeted that its midwifery and reproductive health services were still available “24/7” even though there was no electricity in the camps.

“Midwives and case workers have weathered the storms and walked on slippery and waterlogged roads to our facilities,” its office in Bangladesh further reported.

UNICEF/Brian Sokol

Sitting in her bamboo and plastic shelter in a refugee camp in Bangladesh, Rohingya refugee, Maryam, recounts the events that forced her from her home in Myanmar following a sexual assault that left her pregnant at 16 years old.

Reluctance to return

Meanwhile, an agreement signed earlier this month by the UN refugee agency (UNHCR), the UN Development Fund (UNDP) and the Government of Myanmar could pave the way for thousands of Rohingya to return home.

It also will give the two UN entities access to Rakhine State.

Knut Ostby, the UN Resident and Humanitarian Coordinator in Myanmar, said the most important conditions for the safe and voluntary return of the refugees are citizenship rights and an end to violence.

Though resident in Myanmar for centuries, the mostly Muslim Rohingya are stateless.

“There will need to be programmes for reconciliation, for social cohesion. And these will have to be linked to development programmes. It is not enough to deal with this politically,” he told UN News.

However, Rohingya women and girls are wary about going back to Myanmar, according to Ms. Patten.

“They would be prepared to return only if they have full citizenship rights, but they doubt whether that’s possible. They are very realistic about it,” she said, while also echoing their concerns about safety.

“They all seem to request some kind of a UN mission presence in Myanmar should they go back. But they do not look very hopeful. It’s not the first time that there has been this kind of exodus. And for them, there’s simply no trust.”

Ms. Patten said overall, the Rohingya refugees are pinning their hopes on possible action by the UN Security Council.

A delegation of the 15 ambassadors travelled to Bangladesh and Myanmar just ahead of her visit to Cox’s Bazar.

“Now they put a face to the Security Council,” she said. “And they are expecting no less that the members of the Security Council translate their shock and their outrage into concrete action.”

https://news.un.org/en/story/2018/06/1012372

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/legalcode